|

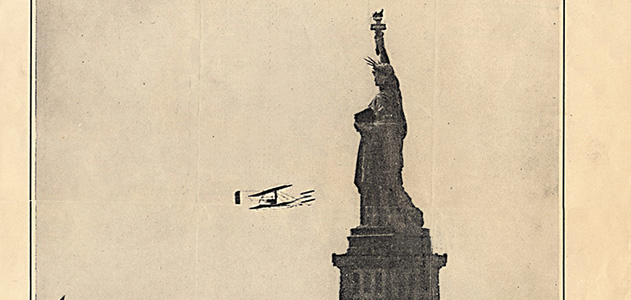

WILBUR WRIGHT GREETS LADY LIBERTY |

Wilbur Wright Greets Lady Liberty

10:20am, September 29th, 1909.

The first over-water flight in American history. | |

LOCATION

Dean Mosher’s epic canvas, Wilbur Wright Greets Lady Liberty, is on display at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum, Early Flight Gallery on the Mall in Washington, DC. The artist is particularly gratified with the placement of his 8' x 10' painting, knowing that few large scale works are accepted. Mr. Mosher has been told he is the only living artist with a large painting on display at the NASM. Mosher spent nearly a decade researching and developing this painting, so to be accepted into the permanent collection of the most-visited museum in the United States is a huge honor on so many levels.

PRINTS AVAILABLE

Collectors and investors can now purchase one of only 100 Signature Centum Series prints of Dean Mosher's epic historical paintings, signed and numbered by the artist. Call 251-928-0900. |

THE STORY BEHIND THE PAINTING

Everyone knows that, after years of research and experimentation, the Wright Brothers were the first to fly, achieving success on December 17, 1903 at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, and that they became known as the inventors of powered flight. What is far less well known is the major struggle the brothers had in achieving recognition for what we consider common knowledge today.

Following their triumph at Kitty Hawk came years of secret research, a brilliant patent attorney (Harry A. Toulmin, Sr.), and frustration as others claimed credit for being the first to fly. Finally, in 1908, with patents granted and confident in the scientific advancements to their flyers, the brothers took to the air with such success in France and America that they became famous overnight.

What followed was a series of spectacular demonstrations, including the subject of this work, but also some serious setbacks. While flying at Fort Myers, Orville had a serious crash that killed his passenger, Lt. Thomas Selfridge, and seriously injured himself. Wilbur took on the legal attacks on their patents, chief among them from Glenn Curtiss, whose constant challenges and appeals were quite wearing on him.

By September of 1909, the Wrights and Curtiss were locked in a very public series of battles both in the courtroom and in the air. Both Wilbur and Curtiss had agreed to fly during the upcoming Hudson-Fulton Celebration in New York, where both men had contracts. Wilbur’s contract promised $15,000 for a flight of at least ten miles or one hour. Curtiss was offered $5,000 if he could complete a round-trip flight from Governors Island up the Hudson to Grant’s Tomb and back. The contest was billed as “the duel of the century” by the press, and both Wilbur and Curtiss were given hangars and Army assistance during the celebration (September 25–October 9).

Curtiss, just returned from France where he had won the Gordon Bennett Cup air race in Reims the month before, was handicapped by his agreement to display his Reims Racer in a New York department store upon his return and so was forced to use an old, now-obsolete flyer for the competition. On the morning of September 29, Curtiss attempted to fly but succeeded in staying aloft over Governors Island for only a few seconds before having to land. He subsequently left the island.

Wilbur arrived shortly thereafter, looked up at the sky, and decided to fly. As the flyer was rolled out, plainly visible underneath was the bright red sixteen-foot “Indian Girl” canoe that Wilbur had seen in the window of the Folsom Arms Company on Broadway a few days earlier. “Indian Girl” canoes were made by the Rushton Canoe Company of Clayton, New York. One of the features of this canoe was that it was constructed of Michigan white cedar and weighed only eighty pounds—about half the weight of a conventional sixteen-foot canoe. Wilbur had added a taut canvas top (attached with hundreds of nails) to the canoe and then secured it under the lower wing, making it the world’s first aerial flotation device.

On his first flight, Wilbur took off at 9 a.m. and flew a two-mile circuit around Governors Island, landed, then decided to go up a second time. At 10:16 a.m., he took off again and headed out over the harbor.

When several reporters and spectators exclaimed, "He's headed for New Jersey!" Charlie Taylor, the Wrights' faithful mechanic, calmly corrected them: "No, he's headed for the Statue of Liberty."

Wilbur steered his flyer between Ellis Island and Bedloe’s Island (renamed Liberty Island in 1956), then began a graceful, arching turn that brought him around to the front of Lady Liberty only a hundred yards away while crowds in Battery Park cheered. On his return leg, he flew near the bow of the outbound Lusitania while a huge crowd on her deck cheered and waved their handkerchiefs. He then landed gracefully, thus adding to his and Orville's many firsts the first successful overwater flight in American history.

Just five days later, Wilbur not only completed his promise of a long flight but also fulfilled Curtiss’s contract to fly up the Hudson River and around Grant’s Tomb and return to Governors Island. Nearly one million spectators observed part of the famous flight as he flew up the Hudson over a large number of American and international warships assembled for the celebration. He was still carrying his red canoe and had now added two small American flags flying from his elevator struts. When he landed thirty-three minutes later, he had made a flight comparable to Louis Blériot's English Channel crossing just two weeks earlier. While Blériot’s thirty-seven–minute flight had ended in a crash landing, Wilbur landed smoothly, then said he was “going to eat some pie."

See Dean Mosher’s other awe-inspiring Wright Brother’s painting, The Bishop’s Boys, commemorating their first flight together, on permanent display at the Carillon Historical Park in Dayton, Ohio. Both paintings are available to purchase as high quality giclees, part of Mosher’s Signature Centum Series, either individually or as a set.

THE RESEARCH

Thanks to the great team that assembled to help me create my first Wright Brothers work, The Bishop’s Boys, most notably Dr. Tom Crouch and Dr. Peter Jacobs of the Smithsonian’s National Air & Space Museum, I had a head start on creating this work. With all the research I had done previously on the Wrights, I became fascinated by Wilbur’s Hudson-Fulton flights and in particular his flight around the Statue of Liberty.

Though there are numerous photos of the plane on Governors Island, Wilbur’s base for his Hudson-Fulton flights, few are extant of him in the air over water. This is a result of limitations of cameras of the day: slower shutter speeds, slower film, lack of long lenses, and the need to be on solid ground (a moving object simply could not be photographed from a rocking boat). This last fact helped me to more accurately pinpoint his position. I discussed this with Dr. Len Bruno at the Library of Congress, and soon afterward he graciously sent me several pertinent Hudson-Fulton documents as well as a large number of articles taken from several newspapers describing the flight.

Though this pile of articles contained a tremendous amount of information, it lacked cohesiveness, so I made six copies of each page, then covered my studio floor and assembled the mass into a dozen complete articles. This helped tremendously, for by assembling complete articles I could separate out the serious journalists from the sensational and pick the handful who had made a real effort to describe the flight accurately. Two had used stopwatches and reported on the distance, position, and altitude with incredible precision. With all this material and modern maps, I was able to create the first complete diagram of Wilbur’s flight path.

Next I focused on the particulars of the flyer itself. Like so many of these flights in different places, one can almost tell where the photo was taken by the minute differences in the skids, canards, rudder, engine, seats—even the number of fluted sections on the radiator (this flyer had six). This flyer had several distinctive features, and even though the canoe is unique to the Hudson-Fulton flights, there were a lot of smaller differences. The half-moon stabilizers had been removed, two blocks on the skids were absent, the cutoff switch cord was reconfigured for easier access because no passengers would be taken on these flights. When I began sending detailed drawings to Dr. Crouch, Mary Mathews, and Amanda Wright Lane, who shared them with other scholars and historians, they were most helpful with their comments.

One troubling piece of information to me was the color of Lady Liberty in 1909. At only 23 did she have an all-over patina or a darkened copper color or perhaps a mottled combination of the two? There would be no color photos of her for years, so I contacted Barry Moreno, one of the fantastic site historians for the National Park Service who care so much about their charges. He quickly produced an article that confirmed that by 1907 she had acquired a lovely green continuous patina. After going through thousands of photos to select the right angle and sun shading for Lady Liberty and a few thousand more to select just the right clouds, I began the painting.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Whenever I undertake to create a work like this, I always say that I am standing on the shoulders of giants. This painting is no exception.

Dr. Len Bruno and Laura Kells assembled for me the entire Library of Congress Wright Brothers collection and gave me one of the greatest honors of my life by letting me hold and carefully look through the private notebooks that Wilbur and Orville carried at Kitty Hawk. The Hudson-Fulton information Dr. Bruno sent me filled in many important gaps, and I particularly appreciate his helping me select photos from the Library of Congress archives.

Dr. Tom Crouch, Senior Curator of the Smithsonian's National Air and Space Museum, as usual, went out of his way to help. It's amazing how gratifying it is to walk into the photo archives of the NASM and have the Senior Curator tell the staff, "Give this man anything he wants!"

Mary Mathews, the retired director of Carillon Historical Park as well as the first chair of the Aviation Heritage Foundation—and one of the leading Wright historians—was invariably helpful and encouraging.

WILBUR WRIGHT AND THE STATUE OF LIBERTY: TEN YEARS OF RESEARCH LEADS TO A PAINTING

WILBUR WRIGHT AND THE STATUE OF LIBERTY: TEN YEARS OF RESEARCH LEADS TO A PAINTING

January 2014, by Dean Mosher | Air & Space Magazine

click to view larger image | | In 2002, when I first learned of Wilbur Wright's 1909 flight around the Statue of Liberty, I knew I wanted to paint the scene. It would take 10 years of research, and I would end up building two models of the Flyer and its controls before I felt able to capture the moment on canvas. By the time I started my painting, which was recently accepted into the National Air and Space Museum's collection, I'd learned the full story behind that historic flight. |

Wilbur Wright had a lot on his mind when he arrived in New York City on September 20, 1909. With him was his mechanic, Charlie Taylor, and a Flyer still crated and ready for assembly. For a celebration honoring the maritime achievements of Henry Hudson and Robert Fulton, Wright had agreed that sometime between September 25 and October 9, he would make a flight that was either at least 10 miles or one hour in duration. In exchange, the city would pay him $15,000. What worried Wilbur that day was that his flights would be over water.

Just a few months earlier, when Wilbur was seriously considering attempting the first airplane crossing of the English Channel, Orville had written him to discourage the flight. The brothers' greatest concern was engine reliability. Wilbur knew that if the engine failed and he had to set down, his skids would bite into the water, throwing him forward into the wires crisscrossing between the forward struts and possibly injuring him. As the wood-and-cloth wings would begin to settle and sink under the weight of the engine, they could drag him down before he could disentangle himself.

So when Wilbur arrived on Governors Island, south of Manhattan, on the morning of September 29, he and Taylor had made a strange modification to the Flyer: Beneath the lower wing, they had slung a bright red canoe, which Wilbur had purchased a few days earlier from the H&D Folsom Arms Company. A top-of-the-line Indian Girl canoe made by the Rushton Canoe Company, it featured a sturdy 16-foot frame made of northern white cedar, which Rushton claimed was nearly a third lighter than other cedars.

The canoe's light weight (approximately 60 pounds) and sturdy construction attracted mostly Adirondack hunters and anglers used to portaging around rapids and waterfalls. Wright was drawn not only by these features but also by the canoe’s aerodynamic shape.To reduce drag, Wilbur had removed the Flyer’s second passenger seatback, and for waterproofing had tightly sealed the open canoe top with nailed-down canvas.

In essence, the canoe turned the Flyer into the world’s first floatplane. Wilbur hoped that in the event the engine failed and the airplane ended up in the water, the canoe would keep the aircraft afloat. With luck, as the airplane glided into the water, the canoe might even hold the craft upright. As the airplane floated, the pilot would have time to extricate himself and swim away. The addition of a life vest next to him, which he could don before swimming clear, suggests that Wilbur had characteristically thought the matter through and come up with a contingency plan.

The Wrights were used to firsts, and this was the first time a pilot would be carrying a large object aloft, so the arrangement needed to be tested for stability. At 9:15 a.m. on September 29 Wilbur ran down the rail built to assist takeoff, positioned into the light westerly breeze, went airborne, made a two-mile flight around the island, and landed safely. Satisfied that the canoe would not impede his ability to control the Flyer, he announced that he would fly again.

At 10:17 a.m., he arose from the rail, which was still oriented into the light west wind, and flew due east. A man in the crowd exclaimed, "I believe he’s off for Philadelphia!" Charlie Taylor calmly corrected him: "No, he will round the Statue of Liberty."

And so he did. Crossing between Ellis and Liberty islands, Wilbur steadily gained altitude, then began a turn to the left, closing the distance to Lady Liberty. At 10:20 a.m., at an altitude of 200 feet, he passed in front of the statue, his wingtips only a few hundred feet from her waist.

He then flew back to Governors Island and landed at 10:22, in view of several hundred thousand spectators in lower Manhattan and the delighted passengers crowding the deck of the outbound Lusitania. On October 4 he would fulfill his contract by flying a distance of more than 20 miles in 33 minutes and 33 seconds.

MOSHER PAINTING ON PERMANENT DISPLAY AT SMITHSONIAN'S NATIONAL AIR & SPACE MUSEUM

August 1st, 2013

click to view larger image | | The artist’s 8’ x 10’ “Wilbur Wright Greets Lady Liberty” canvas was placed on permanent display in the Early Flight Gallery of the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum on the mall in Washington, DC. The artist was there with his wife Pagan and children Megrez and Cleveland. Present were Senior Curator Doctor Tom Crouch and Chief Curator Doctor Peter Jakabs. |

MOSHER PAINTING BOUND FOR THE SMITHSONIAN

May 7th, 2013 by Mike Odom | Fairhope Courier

This past weekend, Amanda Wright-Lane, the great-grandniece of Orville and Wilbur Wright, visited Fairhope to spend time with Mosher and his family. She is a trustee of the Wright Family Foundation of the Dayton Foundation, which works to preserve the story of her family's contribution to aviation history.

"Your house itself is a museum," she said, as she walked through Mosher's living room Friday night, which houses a number of his large historical paintings and other artworks.

The two became friends during his work on the painting, which will soon move from its location in Dayton, Ohio, to its permanent display at the Air and Space Museum.

"The Library of Congress, Smithsonian Archives, Wright State Archives, the Wright Family and the Statue of Liberty Archives all gave me personal access to dig and shift through until the full story emerged," Mosher said. "And I am grateful to them all for this."

"WILBUR WRIGHT GREETS LADY LIBERTY" UNVEILED

May 31st, 2012

Dean Mosher’s canvas “Wilbur Wright Greets Lady Liberty,” depicting the pioneer aviator’s historic flight on September 29, 1909, was unveiled in Dayton, Ohio, on May 31, 2012, as one of the main events commemorating the centennial of the passing of Wilbur Wright.

The unveiling took place at Carillon Historical Park, home of the 1905 Wright Flyer, one of the earliest Wright planes, whose restoration was overseen by Orville Wright shortly before his death in 1948.

Participating in the unveiling were Dr. Thomas D. Crouch, Senior Curator of the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum; Amanda Wright Lane, great-grandniece of Wilbur and Orville Wright; and Mary Mathews, retired Executive Director of Carillon Historical Park and Founding President of the Dayton Aviation Heritage Foundation.

Speakers included Dr. Crouch and Ms. Lane (please click on videos) as well as artist Dean Mosher.

The audience included Rick Young, eminent Wright historian; Dean Alexander, superintendent of the Dayton Aviation Heritage National Historical Park; Stephen Wright, a great-grandnephew of the Wright brothers; and several other Wright scholars and Wright family members.

Following are the video recordings of remarks by Amanda Wright Lane, representing the Wright Family and Dr. Tom D. Crouch, of the Smithsonian Museum.

click here to play video

Video by Scovil Productions | |

Dr. Tom D. Crouch of the Smithsonian Museum.

Senior Curator, Division of Aeronautics. National Air and Space Museum Smithsonian Institution.

Publications: First Flight: The Wright Brothers and the Invention of the Airplane (Washington, D.C.: National Park Service, 2003); With Peter Jakab, The Wright Brothers and the Invention of the Aerial Age (Washington, D.C.: The National Geographic Society, 2003); Wings: A History of Aviation from Kites to the Space Age (New York: W.W. Norton, 2003)

|

|

click here to play video

Video by Scovil Productions | |

Amanda Wright Lane, representitive of the Wright Family.

Amanda Wright Lane is the Great Grand Niece of Orville and Wilbur Wright. Mrs. Lane works to preserve the story of her famous family’s contribution to aviation history. She is a trustee for the Wright Family Foundation of the Dayton Foundation, a 501 (c) 3 charitable fund. It supports the preservation of aviation history related to the lives of the Wright Brothers by funding projects that include research and publication of early aviation history, |

scholarships for studies in the fields of aviation and aeronautics, educational programming, the restoration and display of aviation artifacts, and the development of landmarks and memorials related to the Wrights' story.

CEREMONY HONORING WILBUR WRIGHT

June 1st, 2012

On Friday, June 1, 2012, at 3 p.m., a special ceremony marking the centennial of Wilbur Wright’s passing was held at the Wright family burial plot in Historic Woodland Cemetery, Dayton, Ohio.

Dean and his wife Pagan were special guests of the Wright family. Speakers included Dr. Neil Armstrong in one of his last public appearances; Amanda Wright Lane, great-grandniece of the Wright brothers; Rick Young, eminent Wright historian, and Stephen Wright, great-grandnephew of the Wright brothers. Several hundred spectators attended the thoughtful, uplifting event.

click here to play video

Video by Scovil Productions | |

Neil Armstrong Speaks at the Wilbur Wright Memorial Event

One of Neil Armstrong's last public appearances was at the Wilbur Wright Commemorative Memorial Service of 2012. It was fitting that the first man to set foot on the moon was present to commemorate the man who, along with his brother Orville, started man's quest to break the bounds of earth and reach for the sky.

|

THE WRIGHT "B" EXPERIENCE

On Saturday, June 2, 2012, Dean and Pagan Mosher were invited to join Amanda Wright Lane and Wright family members Margaret Streeter Edwards Brown, Robert Brown, Cynthia Edwards, and Brett Evans at Wright Brothers Airport, Miamisburg, Ohio, to take turns flying in the Wright “B” Experience replica of the historic Wright Model B Flyer. Many thanks to those incredible volunteers who work so hard to keep the Wright legacy alive!

Experience the thrill of pioneer flight with a ride in the Wright “B” Flyer, a modern lookalike of the Wright brothers’ first production airplane.

Based on Dayton-Wright Brothers Airport in Miamisburg, Ohio just south of Dayton, Wright “B” Flyer Inc. operates a fleet of flying and non-flying airplanes built to resemble the Wright Model B, produced by the Wright Company in its West Dayton factory beginning in 1910.

< <

|

|